EEG Validation Study – Home Headband vs Lab Sleep Results

Introduction

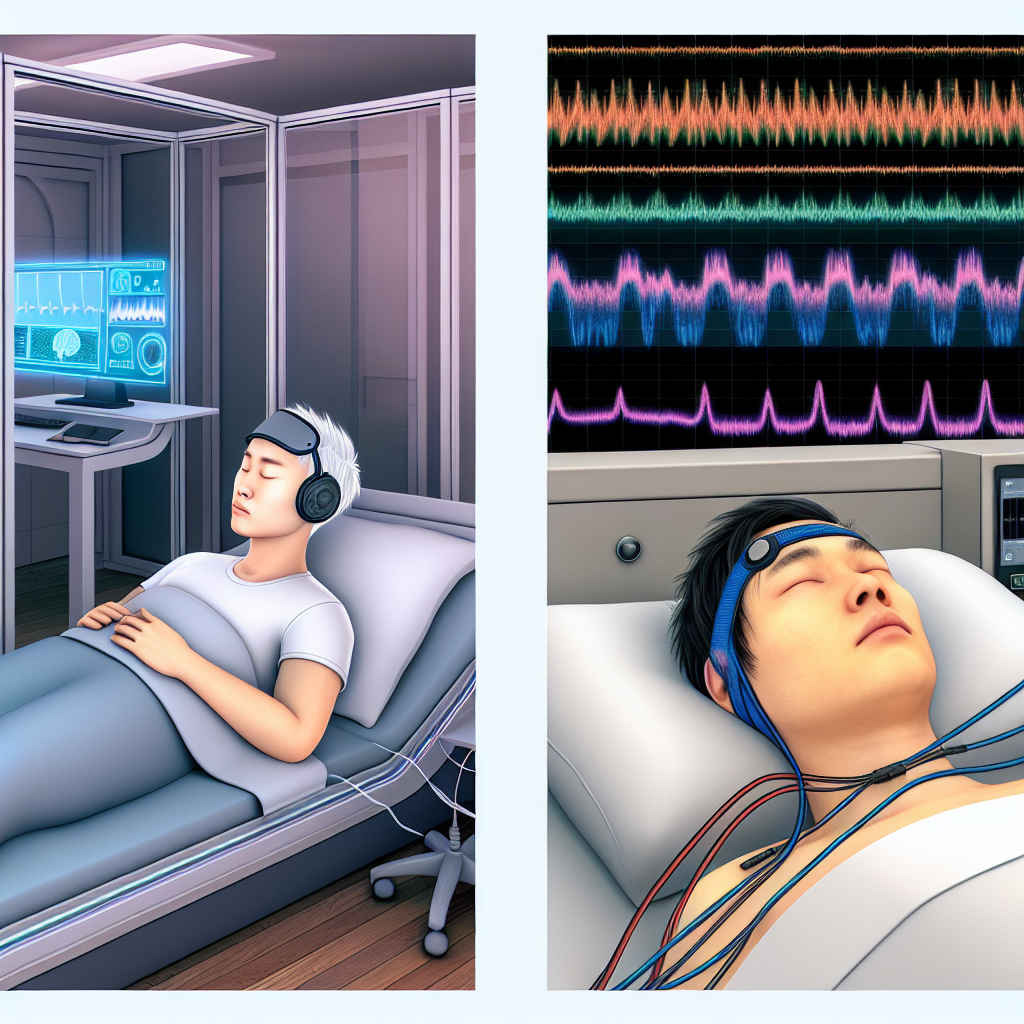

In today’s fast-paced world, sleep has become an invaluable yet increasingly elusive commodity. From school-going children to busy professionals and aging adults, everyone is trying to optimize their sleep. Amid this growing need, **wearable sleep trackers**, particularly EEG-enabled sleep headbands, have surged in popularity. These modern devices promise to deliver clinically relevant **brain wave data**, enabling accurate tracking of sleep stages and providing enhanced sleep diagnostic capabilities from the comfort of home.

A clinical sleep study, or polysomnography (PSG), involves extensive overnight monitoring—including EEG, EOG, EMG, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and respiratory effort. This approach yields comprehensive data on sleep quality and disorders like insomnia, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and parasomnias. However, traditional PSG is costly, time-intensive, and can alter natural sleep behaviors due to the intrusive setup.

This is where consumer-grade headbands such as Dreem, Muse S, and headbands from companies like Philips and Sleep Shepherd come into play. These devices monitor EEG using front-mounted dry electrodes, offering nightly feedback on sleep length, stages (light, deep, and REM), and potentially incorporating features like guided meditations and biofeedback tools.

These devices are more accessible and user-friendly, but how do they compare to clinical PSG? This analysis explores peer-reviewed studies validating these headbands against PSG to understand how accurate and useful they are for sleep health tracking.

Features of EEG Validation Studies: Headbands vs Lab Sleep Testing

Scientific research has increasingly focused on assessing the effectiveness of home EEG headbands compared to traditional PSG to determine their validity in detecting various sleep stages and assessing overall sleep quality.

A landmark study published in the journal Sleep in 2020 by researchers associated with Dreem assessed 25 healthy adults using simultaneous PSG and the Dreem headband. The headlines from this research showed that the Dreem device achieved over 80% accuracy in sleep staging compared to PSG. This substantial agreement highlights significant progress in making at-home EEG tracking clinically reliable.

Another key study in Frontiers in Neuroscience evaluated the Muse S headband. The results showed moderate to high correlations in identifying REM and deep sleep phases between the Muse S and PSG. While Muse S may not yet match PSG in medical diagnostics, it demonstrates sufficient reliability for routine sleep monitoring and sleep stage awareness in the average user.

EEG headbands typically use 2–5 frontopolar dry electrodes, usually placed along the forehead, as opposed to PSG’s comprehensive 10–20 system array. Despite the fewer data channels, these devices use machine learning algorithms and AI-based scorers to make sense of the readings and closely approximate PSG accuracy. Such intelligent software can greatly boost accuracy in sleep staging by analyzing waveform features like spindles and slow waves.

Plasticity of performance is another strength these headbands bring—they allow longitudinal tracking across multiple nights, potentially offering richer insights into chronic conditions or sleep trends. Particularly for people dealing with insomnia or sleep fragmentation, this ongoing access to personalized sleep data provides a more ecological understanding compared to one-off sleep lab assessments.

Further, some advanced headbands now include embedded sleep-enhancing technologies. For instance, certain models deliver auditory stimulation via pink noise, synchronized to enhance slow-wave sleep. Others utilize real-time biofeedback to deter wakefulness or stimulate relaxation, thereby serving a therapeutic role beyond passive monitoring.

Nevertheless, current headbands have limitations. One critical shortfall is their inability to detect respiratory-related conditions like obstructive sleep apnea. Unlike PSG, they don’t measure airflow, oxygen saturation, or thoracic movement—parameters crucial for diagnosing breathing disorders. Therefore, these devices, though validated for sleep staging, are not yet suitable as standalone diagnostic tools for all sleep disorders.

Conclusion

The rapid evolution of EEG-enabled sleep headbands highlights a significant transformation in sleep health self-care and monitoring. Validated by promising studies, these devices closely approximate clinical polysomnography in sleep staging accuracy, particularly for light, deep, and REM phase identification. Their lower cost, convenience, and potential for long-term monitoring make them invaluable for users trying to optimize sleep quality outside of clinical labs.

However, despite their promise, these headbands are not replacements for PSG when respiratory or neurological abnormalities are suspected. Disorders like sleep apnea or narcolepsy demand comprehensive physiological assessments that go beyond EEG.

With ongoing technology improvements, including AI-driven algorithms and integrated neurofeedback systems, the gap between clinical testing and wearable consumer tech is narrowing. Empowering users with accurate, accessible, and actionable sleep data could mark the next frontier in preventive sleep medicine.

Concise Summary

EEG-enabled sleep headbands like Dreem and Muse S offer clinically comparable monitoring of sleep stages when validated against lab-based polysomnography. These consumer devices provide over 80% accuracy in tracking sleep and are ideal for continuous, home-based sleep health assessment. While convenient, affordable, and non-invasive, they cannot detect respiratory sleep disorders like apnea. As AI and sensor technology advance, these devices hold potential as powerful tools for both sleep improvement and early diagnostics, shaping the future of accessible sleep medicine.

References

1. Arnal, P.J. et al. (2020). The Dreem Headband: A Portable Sleep Monitoring Device With Automatic Sleep Staging. Sleep.

2. Krigolson, O.E. et al. (2017). Choosing MUSE: Validation of a Low-Cost, Portable EEG System for ERP Research. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

3. Sleep Foundation. Polysomnography (Sleep Study).

4. Sleep Review Magazine. (2021). Consumer Sleep Technologies vs PSG: Keeping Up With the Times.

5. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Evaluation of Consumer Sleep Devices for Sleep Medicine and Research.

Dominic E. is a passionate filmmaker navigating the exciting intersection of art and science. By day, he delves into the complexities of the human body as a full-time medical writer, meticulously translating intricate medical concepts into accessible and engaging narratives. By night, he explores the boundless realm of cinematic storytelling, crafting narratives that evoke emotion and challenge perspectives.

Film Student and Full-time Medical Writer for ContentVendor.com